This website was created as a project for Genetics 677, an undergraduate course at UW Madison.

Background

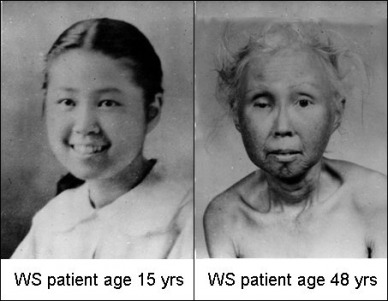

Werner syndrome is characterized as a premature aging disorder, in which affected individuals develop symptoms during puberty and late adolescence that are much more prevalent in elderly people. Eponymous German scientist Otto Werner, who studied four affected siblings for his dissertation, first described the syndrome in 1904. The earliest indication of the disorder is the lack of a growth spurt during adolescence. Some examples of the accelerated features involved with Werner syndrome include cancer, osteoporosis, type II diabetes, ocular cataracts, and atherosclerosis; although these symptoms may not develop until an individual reaches their 20s or 30s (1). Werner syndrome is often called "Progeria of the adult" which is in contrast to Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria, a similar accelerated aging disorder that manifests in early childhood, typically before 12 months of age.

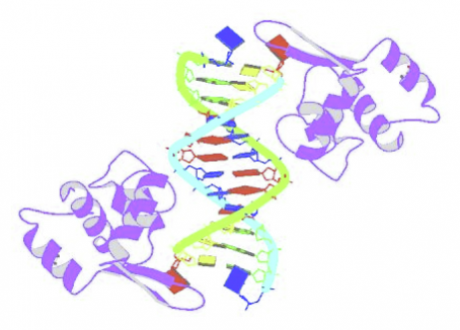

Figure 1. Structure of WRN bound to double-stranded DNA

Gene

The gene associated with 90 percent of Werner syndrome cases is WRN. This gene encodes the Werner protein, located on the short arm of chromosome 8 (locus 8p12-p11.2). The WRN gene is a homolog of E. coli DNA helicase, meaning that they are related by decent from a common ancestral DNA sequence (2). Helicase is an essential motor protein that separates DNA strands, crucial for the function of replication, transcription, and DNA repair. Additionally, mutations affecting WRN helicase activity result in replication-associated telomere loss and chromosome fusion characteristic of Werner syndrome. Telomere loss has been suggested to accelerate cellular senescence, and may be one of the reasons why individuals with Werner syndrome develop premature aging symptoms (3).

Inheritance

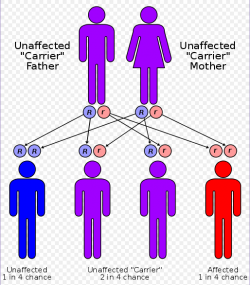

Figure 2

A child inherits genes in pairs (sometimes called alleles), one from each parent. Werner syndrome exhibits autosomal recessive inheritance, meaning that one needs a double dose of the mutation to be affected. If an individual only inherits one mutated copy of WRN, they retain a wild type phenotype for the gene, but will be a carrier for the disorder. The inheritance pattern is illustrated in figure 2 (4). Werner syndrome is extremely rare, with a prevalence rate of approximately 1:1,000,000 - 1:10,000,000. Regions that have shown a higher frequency of Werner syndrome include Japan (1:100,000) and Sardinia (1:200,000), although these estimates should be observed with caution due to small sample sizes (5). Fertility is greatly reduced for individuals with Werner syndrome, possibly due to accelerated loss of priomordial follicles in the ovaries, and testicular atrophy. The most common causes of death among individuals with Werner syndrome are cancer and heart attack, with an average life expectancy of 48 years. Currently there is no cure for the disease, and symptoms are treated as needed, with a greater emphasis on regular screening for symptoms such as diabetes. Preventative measures such as lifestyle counseling are also strongly suggested to reduce the risk of atherosclerosis and other secondary complications (1). The goal of this website is to provide a genetic analysis of WRN and examine it's effect on protein structure and function in those affected by Werner syndrome.

References

1. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Werner Syndrome. Review. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; March 2007. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=werner

2. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Werner Syndrome;WRN. Overview. Baltimore (MA): Johns Hopkins University; April 2007. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=277700

3. Crabbe L, Jauch A, Naeger CM, Holtgreve-Grez H, et al. (2007) Telomere dysfunction as a cause of genomic instability in Werner syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(7):2205-10. PMID: 17284601

4. (Figure 2) Autosomal recessive diagram. Retrieved February 1, 2010 from: http://www.actionbioscience.org/genomic/figures/siegal1.gif

5. Masala MV, Scapaticci S, Olivieri C, Pirodda C, et al. (2007) Epidemiology and clinical aspects of Werner's syndrome in North Sardinia: description of a cluster. Eur J Dermatol 17(3):213-6. PMID: 17478382

6. (Title Figure) Werner syndrome. Retrieved January 28, 2010 from: http://www.scripps.edu/~jjperry/WS.jpg

7. (Figure 1) WRN protein. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/images.do?structureId=3AAF

2. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Werner Syndrome;WRN. Overview. Baltimore (MA): Johns Hopkins University; April 2007. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=277700

3. Crabbe L, Jauch A, Naeger CM, Holtgreve-Grez H, et al. (2007) Telomere dysfunction as a cause of genomic instability in Werner syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(7):2205-10. PMID: 17284601

4. (Figure 2) Autosomal recessive diagram. Retrieved February 1, 2010 from: http://www.actionbioscience.org/genomic/figures/siegal1.gif

5. Masala MV, Scapaticci S, Olivieri C, Pirodda C, et al. (2007) Epidemiology and clinical aspects of Werner's syndrome in North Sardinia: description of a cluster. Eur J Dermatol 17(3):213-6. PMID: 17478382

6. (Title Figure) Werner syndrome. Retrieved January 28, 2010 from: http://www.scripps.edu/~jjperry/WS.jpg

7. (Figure 1) WRN protein. Retrieved March 13, 2010 from: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/images.do?structureId=3AAF